Introduction

Intermolecular forces are weaker than chemical bonds but are essential for understanding physical properties. These are the major kinds of such forces, arranged in order of decreasing strength:

ion–dipole > hydrogen bonding > dipole–dipole > dipole–induced-dipole > London dispersion forces.

In common practice, we consider 3 kinds of forces: ion-dipole, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces (van der Waals was a very influential physicist). The van der Waals forces are of three types: dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, London dispersion.

Electron Density

Before beginning, let’s define a term: electron density. Remember electron cloud? Well, in molecules there are often shared electrons that leave their bond regions in way, and transfer to some other part of the molecule.

Think of it this way: an electron cloud is the common living room of two joint houses. There are several houses in a chain, joined to the ones beside them. Electrons, being “playful” sometimes go to a living room not joint to their own house (atom), due to some effects that are caused by the unique nature of the bonded atoms (electronegativity, resonance, inductive effect, etc.).

When electrons move to some other region, there are more electrons in that space. Consequently, the electron density near that atom is higher.

London Dispersion Forces

London Dispersion Forces

These are present in all molecules even if they are non-polar.

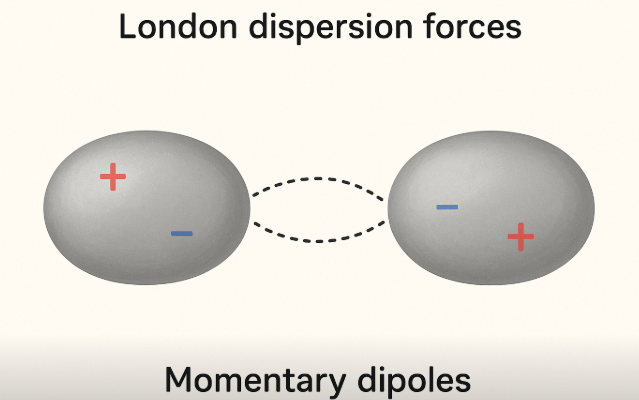

They arise due to temporary fluctuations in electron density which create instantaneous dipoles (accumulation of electrons on one side leads to accumulation of positive charge on the other). They are stronger in larger atoms and molecules because larger electron clouds are easier to distort.

The two ellipse represent the shape of the molecule as a whole, present as dipoles that are temporary (electrons constantly moving around).

Dipole–Dipole Interactions

These occur between polar molecules with permanent dipoles. The positive end of one molecule attracts the negative end of another. They are stronger than London dispersion forces but weaker than hydrogen bonding.

Example: Hydrogen chloride (HCl) has a higher boiling point than methane (CH₄) because of dipole–dipole attraction. Methane has basically no dipole nature, due to less electronegativity difference between carbon and each of its hydrogen. As such, methane molecules are not very inclined to stick together. On the other hand, Hydrogen Chloride is a polar molecule bearing negative pole on Chlorine and positive pole on Hydrogen. This causes hydrogens of HCl molecules to be attracted to negative chlorines of other HCl molecules and vice-versa.

So, HCl molecules are more likely to stick together. Boiling is the conversion of liquid to gas. Gaseous particles are very free of each other’s influence. To attain HCl as a gas, we need to put more energy (heat) into HCl to overcome the attractive influence of dipole-dipole interactions. Meanwhile, methane does not require such energy, so it’s easier to boil.

Dipole–Induced Dipole Interactions

These occur when a polar molecule distorts the electron cloud of a non-polar molecule, inducing a temporary dipole. They are weaker than dipole–dipole forces but they are important for understanding how gases dissolve in liquids. In water, there is polarity in the H-O-H structure, since O is more electronegative. Due to the dipole formed in water, the charges tend to pull electrons from gaseous molecules that interact with water in the atmosphere, causing these molecules to form attractive forces with water and so the gas gets dissolved in water!

Example: Oxygen gas dissolves in water because the dipole in water induces a temporary dipole in oxygen molecules.

Hydrogen Bonding

This is a special and strong form of dipole–dipole interaction. It occurs when hydrogen is covalently bonded to nitrogen, oxygen or fluorine. Hydrogen bonding is responsible for unusually high boiling points, high surface tension and the stability of many molecular structures.

Examples:

Water can form up to four hydrogen bonds per molecule which explains its high boiling point.

DNA double helix is stabilized by hydrogen bonds. Adenine pairs with thymine by two hydrogen bonds while cytosine pairs with guanine by three hydrogen bonds.

Ion–Dipole Interactions

These occur between ions and polar molecules and are stronger than hydrogen bonds because they involve a full ionic charge interacting with a dipole.

Example: When sodium chloride (NaCl) dissolves in water, Na⁺ is surrounded by the oxygen atoms of water molecules and Cl⁻ is surrounded by the hydrogen atoms. Oxygen atoms are partially negative, while hydrogen atoms are partially positive. As such, there are electrostatic forces between these and sodium/chloride ions which tend to keep the atoms of NaCl separated in solution.

This behavior of water is often termed as its dielectric nature, because water molecules tend to induce dipoles (cause charges to partially separate) in other molecules.

Conclusion

This was a very brief explanation of the intermolecular forces, and you are not expected to grapple all of their applications immediately. However, having this slight context is very useful for remembering the nature and physics properties of many coordinate compounds, organic compounds, and complex compounds.

Leave a comment