Introduction

For the most of middle school (and senior school), we focus on the chemical bonds between atoms. These bonds create molecules. However, in higher chemistry we also care about how these molecules behave with each other. While studying states of matter, we always talk about intermolecular forces of attraction. What are these? Of course they are not gravitational forces, but something much, much stronger.

Molecular interaction

Molecules may appear isolated in structural diagrams, but in reality they constantly interact with one another. These interactions are called intermolecular forces (IMFs) and they play a key role in deciding whether a substance exists as a solid, liquid or gas. They also influence properties such as boiling point, melting point, solubility and surface tension.

Before studying IMFs in detail, it is important to understand some things called dipoles and dipole moments.

Dipoles

Lets start with polarity– it is when there is a bond between 2 different atoms, and one of these pulls the shared electrons towards itself with more power than the other. If this atom manages to completely take the shared electrons, there is a complete transfer of electrons and it becomes negatively charged (anion), whereas the other becomes a cation. Yes, these are ionic bonds. They are formed between metals and non-metals (NaCl, KCl, CaO, etc.)

This tendency of an atom to pull electrons in a bond, is called electronegativity.

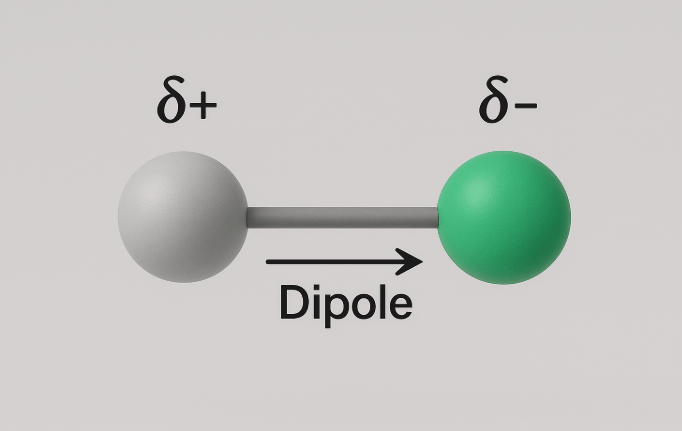

A dipole occurs when electrons in a bond are shared unequally because one atom is more electronegative than the other. This unequal sharing creates a partial negative charge (δ⁻) on one atom and a partial positive charge (δ⁺) on the other. The extent to which this charge (electron) is separated is called polarity. Ionic bonds are the most polar, and non-polar covalent bonds (such as in H2) are least, since both hydrogen atoms are identical and so they pull against each other equally.

The dipole moment (μ) is a vector quantity that measures the polarity of a bond or molecule:

μ = q x d

where q is the magnitude of the partial charge and d is the distance between the charges. Let us not worry about the math.

For ionic compounds, it is easy to understand how dipoles exist (one positively charged atom, the other is negatively charged). The two poles exist together due to being attracted to the opposite charges on each other (opposites attract!)

What about some covalent compounds? Let us consider hydrogen chloride (HCl, also known as hydrochloric acid).

Chorine is one the most electronegative atoms, so it pulls electrons towards it very strongly. On account of this, there is a separation of charges, chlorine is slightly more negatively charged than hydrogen. Right now, we are seeing them as two spheres. However, since the two electrons are closer to chlorine, the electron cloud is more towards chlorine and so the whole molecule is not symmetrical. The electron cloud is just a small packet of space between two bonded atoms, where their shared electrons like to roam.

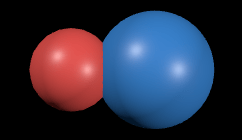

Consequently, the shape of the HCl molecule is not a symmetrical sphere, instead it is more like:

with the bigger sphere being chlorine. Now, imagine sooo many of these molecules sooo close to each other, all bearing a positive charge side and a negative charge side. What if they collide? Positive-Positive collisions, Negative-Negative collisions would repel, and Negative-Positive collisions would attract. So, when such a large number of polar molecules are close to each other and constantly moving, there are bound to be a lot forces between them. These are some of the Intermolecular Forces we are concerned with.

Conclusion

In the forthcoming articles, we shall dive into the types of intermolecular forces, and how they play out in different commonly-known molecules.

Leave a comment