Preamble

When dealing with Vectors, there are four foundations one must build. As long as your pillars are strong, you ceiling will never collapse!

Usually when given a group of vectors, we imagine them to exist in a Cartesian Plane. A cartesian plane just means the coordinate grid (XY-Plane) that you are familiar with. If you wish, we can also use Cartesian Coordinates, i.e. a 3 dimensional region (3D geometry). Right now let us stick to only 2 dimensions.

Vector Components

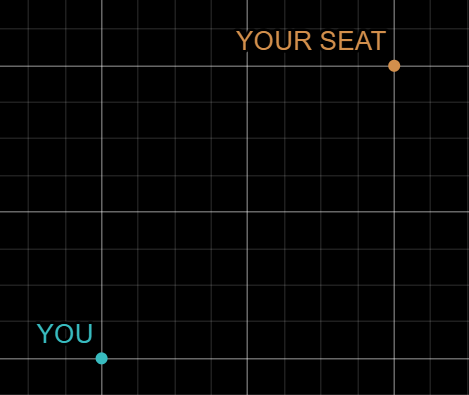

Suppose you’re standing in the center of an exam hall and you have to make your way to your seat. You can’t move across seats, you must navigate through them.

Each square represents a desk, and the grid lines are the spaces between them. Now, there are a lot of paths you can take to reach your seat. What is the shortest path? Of course it’s a straight line! But you can’t move diagonally remember? Only up/down or left/right. Why? Because all x and y coordinates represent a distance from the origin and so the frame of reference is origin, and we are the observer so the origin should be at our location.

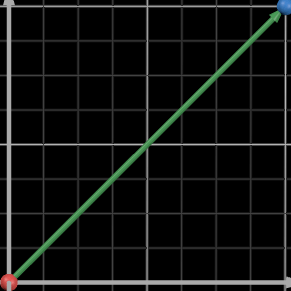

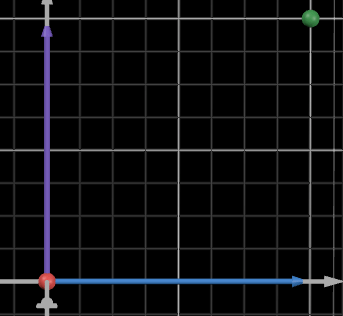

Next, let us sketch

out the straight line

anyway for reference.

This line is vector, as it has both

magnitude and a direction.

It is the displacement vector.

Let us call it S.

Now, notice that this XY plane comprises of 2 dimensions, i.e. 2 directions (right and up). This means that to move across it, one must step right and step up. Moving diagonally is essentially stepping right and up at the same time, so that both x and y coordinates change simultaneously. So that means our S vector is actually a combination of right and up steps! To reach our seat, we need to move 8 units right and 8 units up. So, if we can use our steps to make this vector a straight line, we can use this straight line vector to decompose it into its constituent steps!

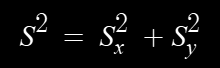

These are called component vectors, yes they are also vectors (remember what they represent!). Lets called these S(x) and S(y), meaning the x component of S and y component of S respectively. From Pythagorean Theorem:

or

Notice that we have not used an arrow in these equations. This is because these equations talk about the magnitude of the resulting vector only. The direction is found by alternative means.

Adding Vectors

Lets reverse our approach. In this scenario, we have 2 directions we can move in – up and right (and down/left but since we need to get to our seat fast, we want the path with the least backtracking). So, we must find a combination of ups and rights that gets us where we need to go.

Firstly, remember that right and up are two different dimensions, i.e. in this P.O.V. you cannot find 2 components to divide the up direction into, such that one of them points right. Moving up will in no way change your position on the horizontal access.

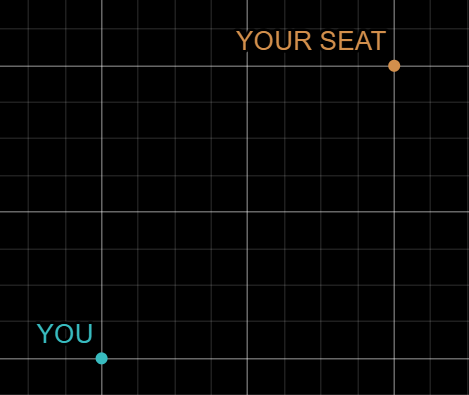

Now, the horizontal distance from our seat is 2 big squares = 2 units on x axis. Similarly, vertical distance = 2 units on y axis.

Let’s represent these displacements as vectors.

We have S(x) = 2 on x axis, S(y) = 2 on y axis.

This looks familiar! These are the components of S. Hence, by putting together the two vectors we get S. This is called vector addition and we write it as: S(x) + S(y) = S

By now it should be clear that this isn’t direct addition. In the previous section we discovered how the magnitude of S depends on its components, using Pythagorean theorem. This equation is merely nominal, i.e. it serves as a concept, not calculation.

You could venture this yourself, by adding a little bit of distance on x axis, and a little on the y axis we get a resulting position, which is a combination of the two and not a summation. It is like saying the x coordinate and the y coordinate of a point taken together give its position (x,y), which is NOT (x+y).

Conclusion

This article covers vector components and addition of vectors. The next article shall wrap up the introduction to vectors, with a mathematics-driven exploration of vector multiplication.

Leave a comment