The best place to start is always the beginning. What is all this and how does it work?

Preamble:

Prerequisites: basic knowledge of SI units and kinematic quantities- mass, displacement/distance, force, velocity/speed, and acceleration. Scalar/Vector quantities and calculus are not required to understand this article.

In everyday world, we take the meaning of certain words for granted- weight, mass, speed, distance, work, power, etc. In physics however, it is important to note that these quantities are very specifically defined, and it is necessary to have those definitions.

This article covers a part of physics called Mechanics. Mechanics is further classified into the study of objects at rest (Statics), and in motion (Kinematics). However, we will aim to look over various concepts intuitively, because they extend to various fields in physics and are essential to connecting with them.

Note – we will avoid hefty derivations, however if you wish you may read them in detail in the provided links.

The concept of matter is one everyone is familiar with. The purpose of this section is to explain how to approach problems in physics. Often when you are given a system (a group of objects that you are examining at once), it consists of many particles (bundles of mass that for all mathematical purposes are taken as the simplest quantity of matter). It is good to remember that particles are not necessarily a specific type of matter. Depending on the situation they can refer to atoms, molecules, quarks, electrons, or even charges.

Let’s begin

The second point we should know is that all motion is relative, meaning it depends on who is watching. The best example of this is standing inside a stationary train and looking out to see another train pass by. You can all imagine that. Now imagine that your train is also moving in the opposite direction. The other train seems to be going away faster. Reexamine the situation but in the same direction– the train seems to be going away slower; it might even seem stationary! This is an extension of relative motion called relative velocity.

Laws of Motion

Enter the shining star of kinematics- Isaac Newton. One can go on and on about him for hours. If you’re not a big fan of the history of science (though you should be), the following is all you need to remember:

Newton gave three fundamental laws governing motions of objects. These laws pertain mostly to a subtype of the general case- linear motion or motion in one dimension, though that does not take away from their essence in any way (we can always find a part of our system which is behaving in one dimension and apply the laws there. This will be covered in the concept of vectors).

First Law of Motion – An object maintains its motion in straight line with a constant velocity unless acted upon by an external force.

This means when net external force F = 0, the object is effectively in dynamic equilibrium and maintains that state. In the special case of v = 0, the object remains at rest and the situation is called static equilibrium.

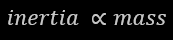

This law is important because it tells us that things tend to be harder to move when they are heavier. Now, we have a fact- there is a property of a body that tells us how likely it is for a specific amount of force to deviate it from its path. We have not yet adopted technical terminology. This property is called inertia, and by Newton’s First Law we know that inertia increases as mass increases. We write this as:

This means if mass increases, inertia increases in a similar way. This is called proportionality. Inertia is proportional to mass. Now here is another fun fact: for objects moving in straight lines in any number of dimensions, inertia = mass of the object. This is why you have probably never used inertia as a quantity in your calculations (you directly take inertia = mass = m). Why is this special? Later, when diving into circular motions, you will see that the inertia in those cases is not equal to mass, but variable.

Second Law of Motion – The rate of change of momentum is proportional to the force acting on a body, and the change in momentum is in the direction of the force.

OK! These are heavy words. Let’s go one by one.

You have probably heard that to make long jumps, you need to get a run-up to build “momentum”. Alternately, some people give life advice along the lines of “start and slowly you will build momentum, and it will become easier to maintain discipline”. If this is the case, you already know what momentum is intuitively! It is a measure of the tendency of an object to be in its state of motion. Again this seems like inertia (indeed it is). Before we proceed let’s get one thing clear: there are different types of momentum in physics. Here, Newton talks about linear momentum (momentum in a straight line).

Now, the faster you’re running, the harder it is for you to suddenly stop. This means momentum is like inertia, but it also accounts for your speed (velocity). So, we define linear momentum as

p = mv

Where v is the velocity of the object, and m is its mass.

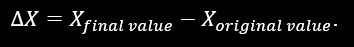

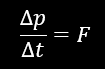

Newton’s law says that rate of change of momentum is proportional to force. Rate of change in physics generally means change in a quantity with respect to time (how much it changes per second). Further, we represent change in X as:

So, we have:

The second part of the law just says that the momentum will try to be in the same direction as the force. Suppose you push a toy car forward. Your force is directed forward, and so the car will have momentum in the forward direction (it will move forward). Conversely, if the car is coming towards you and you block it with your hand, your force is applied in the opposite direction to the momentum. The car’s momentum will shift in that direction and so it might slow down or even stop if you push hard enough.

Through some simple derivation we get:

F = ma

Where a is the acceleration on the object. This formula is the most well-known formula in all of mechanics.

Third Law of Motion – An action always has an equal and opposite reaction, action and reaction act on different objects.

Everyone must have heard this law in some way or the other. One should understand that this doesn’t mean for every action there’s an additional reaction. In every system (environment), when a force is applied in any way (gravitation, mechanical, electromagnetic, etc.), An opposite force always exists. Some force in the system would be acting as a reaction to the initial one, i.e. the reaction force exists, and is not created out of thin air. We shall discuss these specifics more in detail when we cover Thermodynamics.

Most notable ways to visualize these forces would be from collisions, rowing the oars of a boat against the river, walking (you push the ground to move forward), and helicopters (lift).

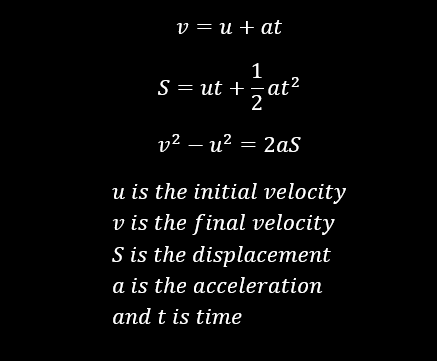

Before ending this article, below are the equations of motion (for more information, refer to the link below):

Leave a comment